by Facilitation Expert | Feb 23, 2017 | Communication Skills, Meeting Support

Research by the National Speakers’ Association shows that becoming more facilitative (i.e., more interactive or service-oriented) is the single most important change a speaker or presenter can make. Following, you will find three powerful presenter tips to use before, during, and after presentations.

If you have not compiled a personal handbook with presenter tips about your personal approach, do so now. Consider keeping prior handouts and slides, agendas, a master glossary, and evaluation summaries. Continuously improve your agendas and capture detailed annotations for the agenda steps you frequently use in events, meetings, and presentations. Especially document complex challenges requiring brainstorming, decision-making, prioritization, and so on. Reflect on the speaking environment and organizational culture to determine when certain tools work best or fail. Your handbook ought to be dynamic, organized, and useful.

The use of interaction, discussion, and structure enlivens participants’ ideas and reactions. In the role of a speaker, embrace the following presenter tips to ensure your presentations shine!

1. Before TIPs

Take extra caution to precisely articulate your presentation’s purpose, scope, and objectives.

-

- Do not rely on a vague and dull purpose statement such as to “educate” or “inform”. With instant, worldwide online access, there are far more effective ways to become informed and learn new material than to attend a live presentation. Presentations are normally intended to shape and guide behavior. WHICH behaviors and WHAT decisions need to be made that will affect or impact your audience?

- Stipulate the scope of your presentation to help manage time and keep your audience focused. What should be included and more importantly, NOT included? Scope represents the boundaries of your presentation and subsequent discussion.

- Consider your statement of presentation objectives as a discrete package you could document and hand off to somebody. If I was unable to attend your presentation but you could hand me the benefits, what would they be?

Provide a comprehensive pre-read that stresses the questions your presentation addresses. Add some structure including selective ground rules to get more done, faster. Consider an attractive presentation template. Specific participant behavioral guidelines you may want to encourage (listed alphabetically):

-

-

- Caution participants about voice inflections that may indicate disdain or an otherwise counterproductive attitude

- Let each person respond without interruption

- Share in accepting post-meeting follow-up assignments

- Stay on topic and agenda, begin and end on time

- Welcome conflict but separate issues from personalities

2. During TIPs

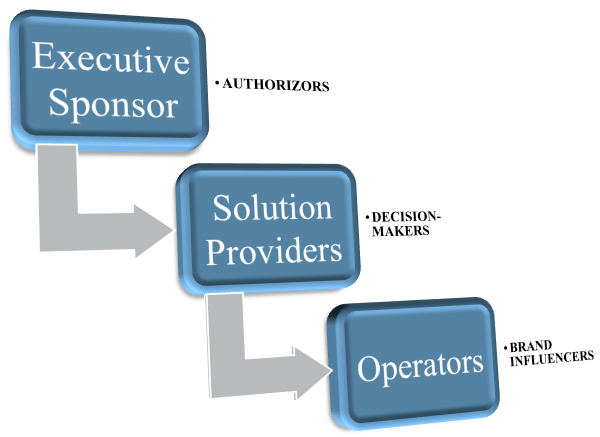

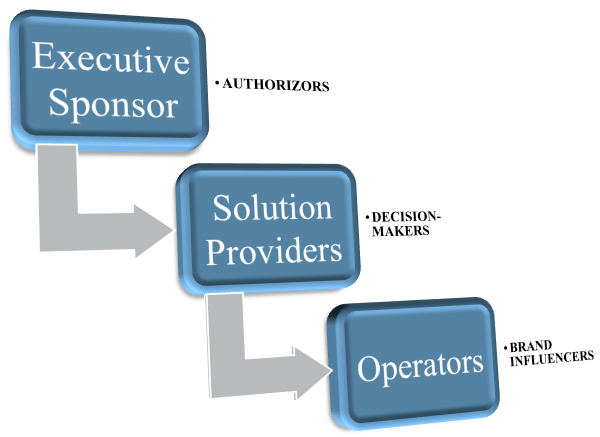

Remember that the business audience for most topics (i.e., those more complicated than individual, private decisions) should consider three different perspectives, Each type of business participant needs their own scorecard or method of measuring the input received from your presentation. Most organizations operate with a solution sponsor, a financial decision-maker (accountable for final approval), and an operator (primary user of the product, system, or solution):

-

-

Presenter Tips to Be More Effective: Organizational Decision-Making

The solution sponsor is held responsible for the identification of solutions and getting the results sought by executive sponsors. Sponsors may decide alone or with a project or product team. They frequently approve the solution concept, request funding, and make a commitment to the results and benefits that will be accrued. In a hospital setting, for example, the solution sponsors may be the directors of finance and/ or radiology.

- Executive sponsor(s} represent the person or group of individuals who authorize solutions. They really do not want to attend more presentations or view more data; they simply want results. For example, in a hospital setting, the sponsor might be the vice president of HIS (health information systems).

- Individuals who will operate the new solution (e.g., a new MRI system) and likely have a strong voice in the brand and model selected. In a medical setting, the operator may include radiologists or radiology technicians. They could be responsible for moving patients in and out of the MRI as quickly as possible while transferring patient images and information to the appropriate diagnostician.

Presenter Tips During Presentations

Especially when time-constrained, encourage audience participants to interact with you as if their message delivered results to someone’s voicemail. Alternatively, encourage responses that would fit on a single 4X6 notecard. Have participants use actual notecards for scripting their “voicemail,” stressing the main points. Encourage them to get to the question or main point by the second sentence.

3. After TIPs

When questions are asked after your presentation, be more facilitative by repeating the questions and comments loud enough so that everyone can hear and respond as appropriate. Use an easel or whiteboard to reflect the input of your participants so that everyone can absorb the comments provided by other participants. Visual reflection frequently outperforms auditory reflection for impact and memory retention.

Consider our Guardian of Change tool to build a consensual understanding of what the presentation means to everyone. Presumably, you want all the meeting participants to depart with a message that sounds like they were in the same presentation together. The Guardian of Change tool helps generate comparable rhetoric and harmonious actions. You certainly don’t want participants in the hallway to sound and behave as if they were in different meetings together.

Presenter Tips After Presentations

Consider some variant of a Plus-Delta or a more robust anecdotal evaluation template that assesses the effectiveness of you and the meeting. A tool that moderates between the two is shown below. It provides numerical feedback but relies on three questions and optional, anecdotal feedback. The questions shown are solid but also illustrative. Do not hesitate to substitute questions that provide you more value, yet rely on a similar format. With this template, you can print two per sheet, reducing the visual burden on your participants by keeping it small.

Moderately Robust Tool for Performance Assessment

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Feb 16, 2017 | Leadership Skills, Meeting Support, Meeting Tools, Prioritizing

Triple constraint theory suggests that it is not realistic to expect to build the fastest, the cheapest, and the highest quality. Something has to “give.”

Yet, most executive sponsors and product owners want all three at the same time. Triple constraint theory tells us that time, cost, and quality are the three most important considerations. However, we need to remain more or less flexible with one of them; either time, cost, or quality. To help your project team understand the tradeoffs that need to be made, consider building a Flexibility Matrix.

A Flexibility Matrix concedes that the three components of triple constraint theory include Time, Cost, and Quality, combined as risk. Consequently, the matrix format allows for differentiation by determining the most and least flexible factors of a product, project, or initiative. The result helps guide consistent decision-making among all team members.

Purpose of a Flexibility Matrix Makes the Triple Constraint Theory Sensible

All sponsors want the best, the fastest, and the cheapest but something has to give — triple constraint theory. You could never ask an executive sponsor ‘which is most important?’ because they would answer “All of them”. Therefore, concede that quality, speed, and price are all most important (i.e., factors of risk), but seek to understand where you have the most amount of flexibility, and conversely, the least amount of flexibility; ergo, a Flexibility Matrix.

Method for Building a Flexibility Matrix to Manage Around Triple Constraint Theory

Since the sponsor may not give you their preferences, have the team build one. Understand that the Flexibility Matrix captures assumptions that support decisions the group makes.

Build your definitions in advance and define or explain the terms time, cost, and quality for your situation. Be certain to work the bookends and ask the team where we have the most amount of flexibility. Then the least? You know the moderate box by default since it is the only blank remaining.

Importantly, after you have created the visual matrix, have the team convert each checkmark into a narrative sentence or statement, for example:

- The schedule is the least flexible because we must have the release ready by October 1.

- Quality (scope) is the most flexible because we can release an upgrade or modification after December 1.

- Resources and cost offer a moderate amount of flexibility.

Flexibility Matrix Allows for Triple Constraint Theory

Make sure you fully define time, cost, and quality in advance of the facilitated session. For example, if you are deciding on the criteria to support a decision about where to locate a landfill (i.e., garbage dump), you might define time as when the landfill opens, cost as the total cost of ownership, and quality as the impact on the environment. As such, the “answer” would likely be the opposite of the chart shown above. “Time” would represent the greatest flexibility and “quality” the least flexibility. Write us with questions you may have and we promise a prompt response.

Build the Flexibility Matrix into your product visions or product charters making it easier to determine work breakdown structure (WBS)

You can create additional time for yourself by facilitating product visions and team charters with members who build their own activities and support requirements to help you reach your objectives and key results. Thus, the Tools (below in italics) will help you build more robust product visions, team charters, and project plans. Additionally, for your benefit, each link takes you to more detailed explanations supported by a specific method including the activities that will deliver your desired output.

Facilitating Product Visions and Team Charters

Facilitating Product Visions and Team Charters Using the Triple Constraint Theory

Tools to facilitating product visions and team charters that generate the step-by-step deliverables for most planning efforts include:

- Business case, project purpose, or opportunity statement: Purpose Is To . . . So That

- Project scope or boundaries: Is Not/ Is (alternatively—Context Diagram Workshop, found in the MGRUSH Professional Facilitator Reference Manual)

- Triple Constraints (i.e.; time, cost, and scope/quality): Flexibility Matrix

- Success criteria: SMART Criteria/ Categorizing (through common purpose)

- Opportunity assessment: Situation Analysis (FAST Professional proprietary and quantitative SWOT analysis)

- Assigned activities (high-level): Roles and Responsibilities (e.g., RASI)

- Team selection: Interviewing Controls/ Managing Expectations

Project Plan — Work Breakdown Structure

The work breakdown structure follows a facilitative approach. Consequently, it supports a consensually agreed-upon plan of action:

- Target audience/ other affected stakeholders: Brainstorming

- WBS (work breakdown structure):

Moving from WHAT (i.e., abstract) to HOW (i.e., concrete)

- Detailed measure of success: Success Measures

- Assigned activities (detailed-level):

Roles and Responsibilities

- Budget, timeline, and resource alignment: Alignment

- Stage gates and milestones: After Action Review

- Risk assessment and guidelines:

Project Risk Assessment

- Communications Plan: Guardian of Change

- Open issues management: Parking Lot Management

- Issue escalation procedure: Issue Log

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Feb 2, 2017 | Managing Conflict, Meeting Support

Use ground rules to help manage individual and group behavior during meetings and workshops.

You can lead meetings and discussions without ground rules, but did you ever leave an unstructured meeting with a headache? The term “discussion” is rooted similarly to the terms “concussion” and “percussion.” A little bit of structure will ensure that you get more done, fast.

Primary Ground Rules

Consider a few, select ground rules for every meeting, regardless of your situation. We consider the following four ground rules so important we use them in every meeting or workshop. The fifth meeting ground rule shown below (“No Hiding”) has been added for online meetings.

1. Be Here Now

First and foremost, speaks to the removal of distractions and getting participants to focus. “Be Here Now” demands that electronic leashes be reined in—i.e., phones on stun mode, laptops down, be punctual after breaks, and pay attention. The hardest thing to do with a group of smart people is to get them to focus on the same issue at the same time.

Your job is to remove distractions so that they can focus.

2. Consensus means “I can live with it”

We are NOT defining consensus as everyone’s favorite or top choice. Nor are we suggesting that our decisions will make everyone ‘happy.’ We are facilitating to a standard that everyone can professionally support. Participants agree they will NOT try to undermine the results after the meeting ends. If so, they are guilty of displaying a lack of integrity. We strive to build an agreement that is robust enough to be considered valid by everyone. No one should lose any sleep over the results. Remember, however, it may not be their ‘favorite’ course of action.

3. Silence or absence implies consensus

This ground rule applies to structured, for-profit situations and NOT necessarily unstructured, political, or social meetings. During our standard business meetings, participants have a duty to speak up. It remains the primary responsibility of the facilitator to protect all the meeting participants. It is NOT their job to reach down someone’s throat and pull it out of them. If participants have information to bear in a discussion, then it is their responsibility to share it. Participant involvement is their obligation, not simply their opportunity. Their silence speeds us up since we don’t have time to secure an audible from every participant on every point discussed in a meeting. Their silence indicates two positions that need to be stressed by the facilitator, namely:

- They will support it, and

- They will not lose any sleep over it.

If either is not true, shame on them—they are being paid to participate. If they cannot accept their fiduciary responsibility, they should work somewhere integrity is not valued.

4. Make your thinking visible

People do not think causally. They think symptomatically. Two people eating from the same bowl of chili may argue over how “spicy” it is. Note, that they seldom argue about verbs and nouns. Rather they argue about modifiers (e.g., adjectives and adverbs). They subjectively argue about spiciness. To one, the chili is hot. To the other, it is not. They are both right. A great facilitator will get them to ‘objectify’ their discussion so that they both can agree that the chili is 1,400 Scoville Units. They don’t think Scoville Units however, they think ‘hot”. As facilitator you must challenge them to make their thinking visible.

5. No hiding

For video conferences, enforce a rule that prohibits people from turning off their live video stream. When hidden, no one has any idea what they are doing or if they are even listening. Dr. Tufte uses the term “flatland” to describe the two-dimensional view, such as the view of online participants on a screen. Working in flatland makes it difficult enough to observe nonverbal reactions. Culturally, you may need to get participants’ permission to use this rule but don’t back down. Enforce “no hiding.”

Be Here Now — Our Most Popular Meeting Ground Rule

Constantly Reinforce Be Here Now

Simply applying the ground rule Be Here Now won’t alone solve the problem, but it will help, especially if you take the time to explain everything it means to your participants.

Arrow—

- Post a visual agenda and put an arrow or other device on it to indicate where the group is on the agenda. Do not use the check box approach since it is never clear if the group is on the last checked box or the next unchecked box. Shopping mall signs indicate where you are, not where you were.

Consciousness—

- Ask participants to “be here now’ and strive to keep their consciousness focused on listening and contributing. Ask them to stay fresh, and if necessary, take more frequent breaks. Bio-breaks should be offered more frequently in the morning and with virtual meetings (e.g., video presence). Consider 30-second “stretch” breaks every thirty minutes; offering up quick deep knee bends or shoulder turns to keep participants awake and fresh. Some cultures refer to this as a 30-30, and if it is part of your culture, use a timepiece or timer to signal each 30-minute segment.

Leashes—

- Have participants disengage their electronic leashes and beware because the vibration mode does not mean silent, only lower tones. If participants cannot wait to address an electronic request, have them take it out of the room, but do not allow laptops, smartphones, and multitasking. Groups that claim to multi-task, perform mentally at the level of chimpanzees. Do you really want to facilitate a roomful of monkeys?

Punctuality—

- Participants should not arrive late, either at the meeting start or after breaks. Start meetings on time so that you don’t punish the people who attend on time. Use MGRUSH timers to ensure on-time attendance after breaks.

Updates—

- If participants are late or leave the room and then return, do not stop the meeting to give them a personal update. Personal updates penalize the on-time participants. Rather, refresh the tardy participants during the next break or pair them off with somebody and send them to the hallway for a one-on-one update, if the update cannot wait until the next break.

Consistently Demonstrate Be Here Now

To Be Here Now is infectious so lead the way. Arrive early and first. Watch your time closely and call breaks as needed. More is better so that participants can attend to their electronic updates. Most all agree that four 5-minute breaks during a morning session are better than one 20-minute break. Monitor them tightly however and do not allow leakage. Your group depends on you for their success.

Additional Meeting Ground Rules

We refer to other ground rules as ‘situational’. You will vary their use depending on meeting type, participants, deliverables, and timing. Some secondary meeting ground rules we have found particularly effective are shown below. We don’t have space to discuss them all, but our favorites, based on frequency of use, are italicized:

- Be curious about different perspectives

- Bring a problem, bring a solution

- Challenge (or, test) assumptions

- Chime in or chill out

- Discuss undiscussable issues

- Don’t beat a dead horse

- Everyone has wisdom

- Everyone will hear others

and be heard

- Focus on “WHAT” not “HOW”

- Focus on interests, not positions

- Hard on facts, soft on people

- It’s not WHO is right; It’s WHAT is right

- No “Yeah, but”—Make it “Yeah, AND…”

- No big egos or war stories

- Nobody is smarter than everybody

- No praying underneath the table (i.e., texting)

- One conversation at a time (Share airtime)

- Players win games, teams win championships

- Put on Your Sweaters (leave your egos and titles in the hallway)

- Share reasons behind questions and answers

- (or,) Share all relevant information

- Speak for easy listening—headline first, background later

- The team is responsible for the outcome

- The whole is greater

than the sum of the parts

- Topless meetings (i.e., phones on stun, no laptops)

- We need everyone’s wisdom

Brainstorming Ideation Rules

Here is an entirely different set of ideation rules that should be used during the Ideation step of the Brainstorming tool. While covered in detail in another article, we are providing the list below for your convenience. With these ideation rules or any of the above ground rules, do not hesitate to contact us for additional explanations:

- 5-Minute Limit Rule (i.e., ELMO doll — Enough, Let’s Move On)

- Accept the views of others

- All ideas allowed

- Be creative — experiment

- Build on the ideas of others

- Everyone participates

- Fast pacing, high-energy

- No discussion

- No word-smithing

- Passion is good

- Stay focused on the topic

- Suspend judgment, evaluation, and criticism

- The step (or workshop) is informal

- When in doubt, leave it in

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Jan 19, 2017 | Managing Conflict

Most people associate shame or loss of power with being wrong. Ever felt yourself getting defensive? When your meeting participants turn defensive, especially when they feel they are losing ground, neurochemistry hijacks the brain. Because they are addicted to being right, the amygdala, our instinctive brain, takes over. With a focus on being right, participants are unable to regulate emotions or handle the gaps between expectations and reality.

“In situations of high stress, fear, or distrust the hormone and neurotransmitter cortisol flood the brain. Executive functions that help us with advanced thought processes like strategy, trust building, and compassion shut down.”[1]

Scientific studies suggest four responses that every facilitator should expect from meeting participants, namely:

- Fight (keep arguing the point),

- Flight (revert to, and hide behind, group consensus),

- Freeze (disengage from the argument by shutting up)

- Appease (make nice to your adversary by simply agreeing with him)

Addicted to Being Right: Restoring Balance

Addicted To Being Right Requires a Facilitator to Restore Balance

Without facilitation (especially active listening and challenge), the four responses lead to sub-optimal results because they prevent the honest and productive sharing of information and evidence-based proof.

Some suggest that “Fighting” is the most common and most damaging. Can you imagine a professional fight without a referee? Of course not, and the facilitator is the meeting referee. In humans, bio-chemicals drive the urge for “fighting”.

“When you argue and win, your brain floods with different hormones: adrenaline and dopamine, which makes you feel good, dominant, even invincible. It’s the feeling any of us would want to replicate. So the next time we’re in a tense situation, we fight again. We get addicted to being right.”

When these dominating personalities are allowed to take over a meeting, they become unaware of the impact on the people around them. While they are getting high from their dominance, others are being drummed into submission. Group dynamics undergo a strong diminishing of collaboration.

However, oxytocin can make people feel as good as adrenaline. Oxytocin activates connections and opens up the networks in our brains, driving from the prefrontal cortex. When participants feel connected, they open up to sharing and trust.

Addicted to Being Right: Facilitator Tips

Great facilitators seek to amplify the production of oxytocin while striving to avoid spikes of cortisol and adrenaline. Help others who display addiction to being right by embracing some or all of the following suggestions:

- Anticipate and provide appropriate ground rules: Remind everyone that they have a fiduciary responsibility to speak up to support or defend claims

- Avoid judging: focus on issues, not personalities

- Carefully manage scope creep: strongly avoid the tendency for the group to fall into a harmful conversational pattern

- Counteract the domineering: ensure that everyone contributes and consider going around in a circle (ie, ‘round-robin’) or demanding Post-It® notes from everyone with their point of view (again make sure you capture the perspectives visually and transfer small Post-It notes to large format display so that everyone can see all the claims)

- Focus on open-ended questions: Be careful to avoid close-ended questions and force a multitude of open-ended responses

- Listen with empathy: Strive to explore and understand everyone’s perspective as there can be more than one right answer

- Provide visual feedback: Highlight the evidence-based claims (i.e., objective support)

“Connecting and bonding with others trumps conflict. I’ve found that even the best fighters — the proverbial smartest guys in the room — can break their addiction to being right by getting hooked on oxytocin-inducing behavior instead.”

[1] See “Conversational Intelligence: How Great Leaders Build Trust and Get Extraordinary Results” by Judith E. Glaser

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Jan 12, 2017 | Analysis Methods, Decision Making

An After-Action Review (AAR) is an effective tool for debriefing projects, programs, or other initiatives. It may also be considered similar to a Hot Wash, After-Action Debriefing, Look Back, Postmortem, or, in the Agile community, a Retrospective. Regardless of the name, the primary purpose of an AAR is for participants to reflect on what transpired, extract key lessons, and identify opportunities to enhance future performance.

Purpose of an After-Action Review Session

An After-Action Review is NOT intended to critique, grade success, or failure. Rather, it identifies weaknesses that need improvement and strengths that might be sustained.

An After-Action Review answers four “learning culture” questions:

- (Purpose) What was supposed to happen?

- (Results) What did happen?

- (Causes) What caused the difference?

- (Implications) What can we learn from this?

The After-Action Review provides a candid discussion of actual performance results compared to objectives. Hence, the engagement participants contribute their input and perspective. They provide their insight, observation, and questions that help reinforce strengths and identify and correct the deficiencies of the completed project or action.

Learning cultures highly value collaborative inquiry and reflection. Therefore, the U.S. Armed Forces use After-Action Reviews extensively, relying on a variety of means to collect hard, verifiable data to assess performance. The U.S. Army refers to the evidence as “ground truths.”

Participants identify mistakes they made as well as mistakes made by others. They prohibit any other use of candid discussions, including performance reviews.

The U.S. Army’s approach may use five basic guidelines that govern its After-Action Reviews, namely:

Guidelines for an After-Action Review Event, Meeting, or Workshop

- Call it as you see it

- Discover the “ground truth”

- No sugar coating

- No thin or thick skins

- Take thorough notes

After Action Review Focuses on Listening

After-action reviews emphasize openness, candor, and transparency. While complete candor can be difficult for many groups, it’s essential to encourage full disclosure during the process. Participants should identify their own mistakes and share constructive observations about others. It is crucial to make clear that the discussions are confidential and should not be used for purposes like performance evaluations.

An After-Action Review workshop can range from part of a day to a full week, depending on the scope of the initiative. It may involve twenty to thirty participants or more, though not everyone needs to be present simultaneously, allowing for flexible participation throughout the workshop.

Agenda for an After-Action Review Event, Meeting, or Workshop

Begin with the MGRUSH introduction and emphasize the project objectives and expected impact of the project on the organizational holarchy. Carefully articulate and codify key assumptions or constraints.

Results are compared to the SMART objectives. Items that worked or hampered provide input for later discussion. Be immediately cautious about scope creep. Questions that may be out-of-bounds at this time include why certain actions were taken, how stakeholders reacted, why adjustments were made (or not), what assumptions developed, and other questions that need to be managed later.

Compare the project results to the fuzzy goals and other considerations. Be cautious to avoid scope creep. Manage other questions later such as why certain actions were taken, how stakeholders reacted, why adjustments occurred (or not), and what assumptions developed.

Results-focused discussion (or lack thereof) stimulates talk about options and conditions to leverage in future projects.

-

-

-

- How stakeholders reacted

- What assumptions developed

- What worked and hampered

- Why certain actions took priority

- What adjustments worked (or not)

- Other questions as appropriate.

Assess or build a risk management plan and other next steps or actions (e.g., Guardian of Change) based on actual results.

Use the four activities in the MGRUSH review and wrap-up

Special Ground Rules for an After-Action Review Event, Meeting, or Workshop

An AAR workshop can handle more than twenty people, with frequent use of break-out groups. Do not hesitate to partition the workshop so that participants may come and go as required. You may need to loop back, cover material built earlier, and clarify or add to it. Above all, the approach shifts the culture from one where blame is ascribed to one where learning is prized, yet team members willingly remain accountable.

Conduct After-Action Reviews consistently after all significant projects, programs, and initiatives. Therefore, do NOT isolate “failed” or “stressed” projects only. Additionally, ground rules and guidelines that have proven successful in the past include:

- Do NOT judge the success or failure of individuals (i.e.; judge performance, not the person)

- Encourage participants to raise any potentially important issues and lessons

- Focus on the objectives first

For learning organizations

For learning organizations, the following also supports cultural growth:

- Some of the most valuable learning derives from the most stressful situations

- Transform subjective comments and observations into objective learning by converting adjectives such as “quick” into SMART criteria (i.e., Specific, Measurable, Adjustable, Relevant, and Time-Based) such as “less than 30 seconds.”

- Use facilitators who understand the importance of neutrality and do not lecture or preach

- Teach the team to teach itself

Therefore, effective use of After-Action Reviews supports a mindset in organizations that are never satisfied with the status quo—where candid, honest, and open discussion evidences learning as part of the organizational culture. In conclusion, learning is everyone’s responsibility and it begins with hard data used to analyze actual results.

_____

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools and methods daily during the week. While some call this immersion, we call it the road that yields high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Go to the Facilitation Training Store to access proven, in-house resources, including full agendas, break timers, forms, and templates. Also, take a moment to SHARE this article with others.

To Help You Unlock Your Facilitation Potential: Experience Results-Driven Training for Maximum Impact #facilitationtraining #meeting design

______

With Bookmarks no longer a feature in WordPress, we need to append the following for your benefit and reference

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.