by Facilitation Expert | Jan 5, 2017 | Facilitation Skills, Meeting Support

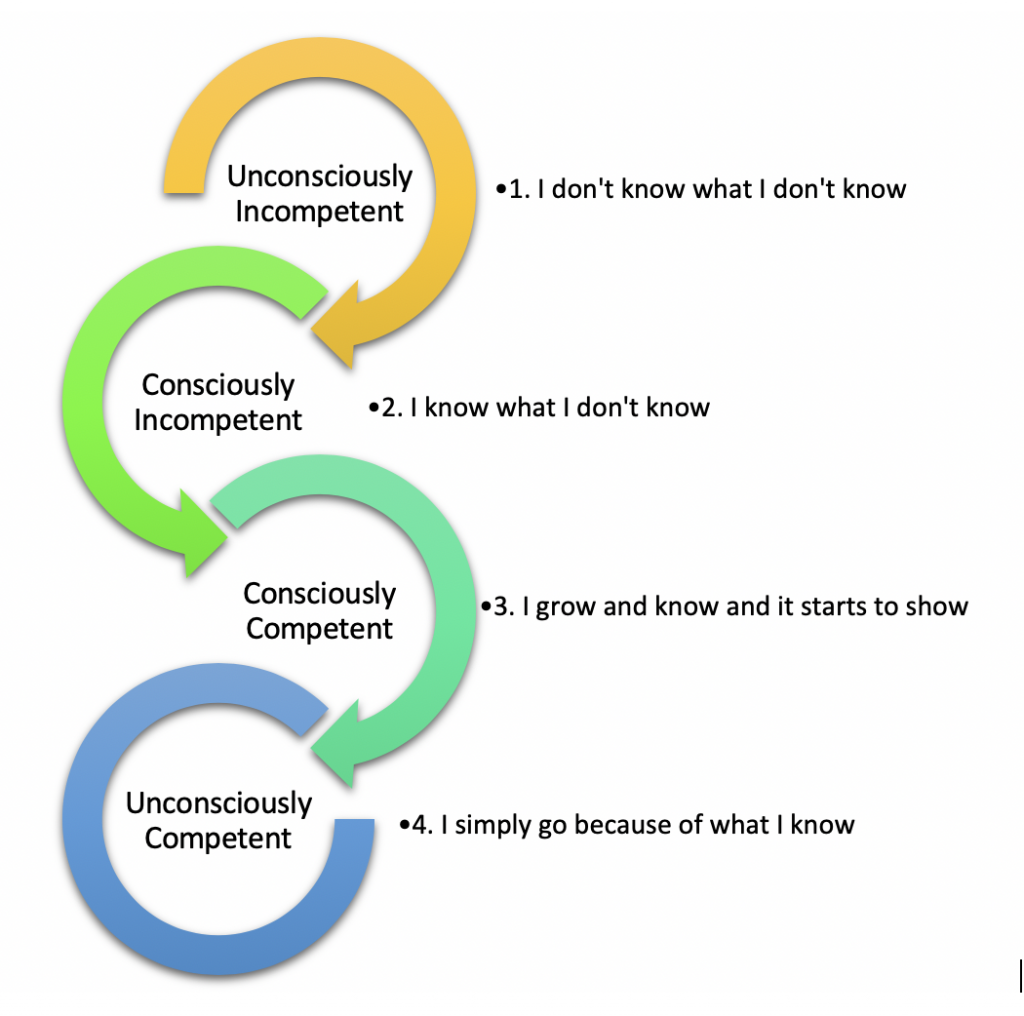

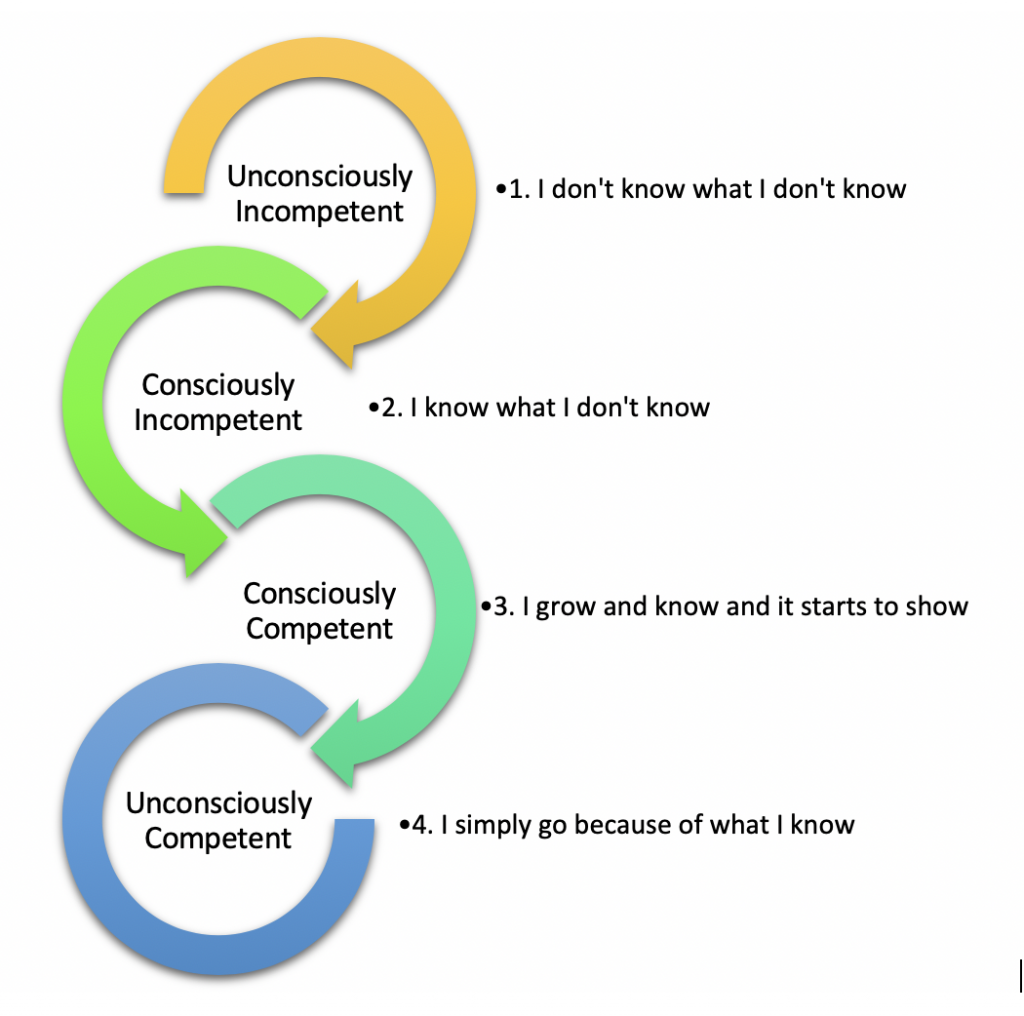

To become an unconsciously competent facilitator, you first become conscious and then competent. As you progress and increase your abilities, you will note an evolution of competency, illustrated in the chart below. First, note that consciousness precedes competence. You do not achieve a consistent level of success until you have developed consciousness about what is required. Secondly, you will discover that the amount of time between each of the stages decreases as you make progress. Let’s look at each of the stages and the aphorisms offered up by John Maxwell that capture the sentiment of each stage.

The Four Stages of Consciousness, Becoming an Unconsciously Competent Facilitator

Unconsciously Incompetent

Before you undertake a complex activity, you slumber through an area of unconscious incompetence. You may linger at this stage for decades. Look at the amount of time it takes to discover the difference between well-run and poorly-run meetings. In this stupor, you “do not know what you do not know.” You lack both knowledge and skills and are unaware of your incapacity.

Consciously Incompetent

Yet another stage remains before you become competent. Here you develop increased consciousness. During this stage, you also develop aspirations and hopes. You begin to envision yourself as competent and contributory. You may linger in this state for a long time, depending on your determination to learn and the real extent to which you accept your incompetence. Most importantly, your consciousness enables you to observe and identify the characteristics of competency, typically in others, as you begin to “know what you don’t know.”

Consciously Competent

Cast into the role of facilitator, you find yourself slipping into and out of competency. You can increase the consistency of your competency by taking formal training, practicing, participating with others who aspire to be better, and obtaining valuable feedback. Developing competence occurs much quicker than developing consciousness. Practice, training, and feedback help because they increase your consciousness. You “grow and know and it starts to show.”

Unconsciously Competent

With repetitive practice and experience, you reach a point where you no longer need to think about what you are doing. You become competent without the significant effort that characterizes the state of conscious competence. You will drift in and out of unconscious competence, based on the skills you master quickly. It takes little time to become unconsciously competent, only practice. Here your services are requested “because of what you know.” Eventually, you know that it feels right and you do it.

Howell (1982) originally describes the four stages:

“Unconscious incompetence – this is the stage where you are not even aware that you do not have a particular competence. Conscious incompetence – this is when you know that you want to learn how to do something but you are incompetent at doing it. Conscious competence – this is when you can achieve this particular task but you are very conscious about everything you do. Unconscious competence – this is when you finally master it and you do not even think about what you have such as when you have learned to ride a bike very successfully”

— (Howell, 1982, p.29-33)

See also: Howell, W.S. (1982). The Empathic Communicator University of Minnesota: Wadsworth Publishing Company

Remember, consciousness precedes competence, and superb competence does not take much time, but it does take practice. We hope you are getting your fair share of challenges and seize the opportunity for more practice and feedback.

For a six-minute video presentation on The Four Stages of Consciousness, turn here.

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Dec 29, 2016 | Meeting Support

Don’t overlook the importance of your meeting documenter or documentation support. The document produced from an MGRUSH workshop provides the raw data for project deliverables. The meeting becomes a waste of time if meeting notes are not clear and accurate.

During lengthy, critical, and modeling workshops, you should solicit support to help with your documentation. It is important that your meeting documenter knows and agrees to their role, functions, and responsibilities.

Illustration by Julia Reich from Stone Soup Creative. A graphic recording approach by a meeting documenter.

Illustration by Julia Reich from Stone Soup Creative. A graphic recording approach by a meeting documenter.Role of Neutrality for a Meeting Documenter

Emphasize to every meeting documenter that they are to remain absolutely neutral—they are part of the methodological team (i.e., context) and are never to interfere with the content during or after sessions.

Co-Facilitating Rotation

If or when co-facilitating, consider sharing roles. Pre-assign select steps to facilitate for each leader. When NOT facilitating, the other person serves as the meeting documenter.

Responsibilities of a Meeting Documenter

The meeting documenter is responsible for ensuring completeness and accuracy. The meeting documenter is also responsible for:

- Ensuring the availability of proper tools and equipment.

- Providing documentation that is properly named, archived, and available for the project team upon completion of the workshop.

- Reading the documentation back to the group for clarification.

- Rehearsing the documentation method before the session.

- Transcribing the documentation with notes, decisions, charts, and matrices from the session.

- The documenter assists the facilitator by capturing participant input that is written on flip charts or whiteboards. Capture photographs of the printed versions to double-check documenter accuracy.

- Use the documenter to hang completed flip chart paper on the wall. This helps you to keep the session moving without distractions. Arrange before the workshop where you expect to hang different sections or deliverables within the agenda.

- When the group develops a definition or major decision during the session, ensure information is accurately and fully captured.

- It is important to note that the documenter copies what the session leader writes onto flip charts, a front wall, or overheads. The documenter does not interpret the discussion, capture complete transcription, or capture random notes.

- The documenter does not judge or evaluate what the group decides. If what they are hearing is unclear, the documenter must ask the session leader to ask the group for clarification and not intervene directly.

Who Makes the Best Meeting Documenter?

A meeting documenter should be easy to work with, willing to keep quiet (i.e., follow the role of content neutrality), have good handwriting, understand the situational terminology, be willing to work for you during the session, and understand the purpose and deliverable of the structured meeting notes. Good documenters can be found typically in three places:

Meeting Documenter

- Trained session leaders frequently make strong documenters. Supporting one another and experience numerous benefits from cross-training, especially for newer facilitators.

- Project members from other, especially related projects. These people understand the terminology and how notes get used (e.g., input to requirements or design specs). They must be chosen carefully because they need to remain quiet and cannot become involved in the discussions.

- New hire trainees or interns provide a win-win opportunity. These people tend to work hard at being good documenters. They frequently have enough background in terminology that they do not get lost in the discussions.

- For purely narrative capture, administrative assistants will work wonders because you have removed them from more mundane activities.

Plan Your Work, Work Your Plan

The relationship between you and the documenter is important because the session leader and documenter comprise the methodological team responsible for generating the final deliverable. Optimally, constant communication between you is essential. Keep the following in mind when working with a documenter:

How to Train Documenters?

The following steps provide a method for training documenters:

- Provide them with a copy of your annotated agenda. Walk through each of the agenda steps, their role, the volume of documentation you expect, and what to do with it. Provide them with examples from prior workshops or deliverables to illustrate how their captured input will be used. Examples can be from previous sessions or created by the session leader, preferably relying upon a metaphor or analogy.

- Documenters often feel intimidated when they see a bunch of templates and do not understand their purpose. Explain the purpose of the deliverables from each question you intend to ask in the workshop. Your MGRUSH Reference Manual includes descriptions of the deliverables from each step in the workshop of the Cookbook Agendas. Your note-taking tools should not get in the way of documentation. Let them modify the format of note-taking if it is appropriate.

- Develop a picture of the final deliverable of the workshop. You can use simple flow-chart or templates or arrows and icons to represent the final document structure. This helps the documenter to move the note-taking out of the abstract into something concrete.

- Walk through the technique and methods with the documenter prior to the session to ensure that that their role is clearly understood—address any questions they have.

- Training does not end with the start of the workshop. During the workshop, check with the documenter often to ensure that there are no problems and that the appropriate outputs are being properly documented.

Checklist for Meeting Documenters

Use this checklist with your documenter to prepare and review.

- Sit where you can see and hear the session leader and what the session leader is writing on visual aids. Preferably, position yourself on the U-shaped table close to the facilitator.

- Have all materials ready before the workshop starts.

- Clear your work area from any distractions.

- Neat handwriting is necessary if you are handwriting.

- Listen to, understand, and be alert for key ideas.

- Give speakers and session leaders careful attention. Do not change meanings to your own. Document the main ideas; the essence of the discussion as taken from the flip charts or other visuals that the session leader is using. Capture the results from the visuals—not complete transcriptions or word by word minutes of the meeting.

- Capture information first—grammar and punctuation later.

- Avoid abbreviations, key, or cue words. Do not change words or meaning.

- Stick to verbatim comments whenever possible.

- Accurately and fully capture the ideas, workflows, outputs, and other components of any models or matrices that are built.

- Seek clarification and review as soon as possible if unsure. Remember—if not documented, it did not happen!

- Control your emotions. If you are reacting to your surroundings or a group member, you cannot listen effectively.

- Stay out of the discussion. Stick to your role. Stay neutral!

Meeting Documenters’ Guidelines

Once you have the right tool and the right documenter, use them properly.

- Always take photographs of handwritten sheets as a back-up.

- Do not attempt to capture documentation real time with the screen displayed to the participants (eg, using a large screen projector hooked up to the terminal). This distracts the participants from the purpose of the meeting (they become enamored with the tool), it forces a low-light condition (which may put some people to sleep), and any mistake, confusion, or slowness of capture is both visible and out of your control (the documenter is doing it).

- Capture process flows or screen layouts and shows them to the participants. First, the session leader draws them on a whiteboard, flip chart, or another manual tool. The documenter captures the layout on a prototyping or mockup tool. When possible, project the finished illustration, diagram, or report on a large screen. If not, take a photograph of the original to re-create offline.

- If you are using a modeling tool (eg, VISIO), have the documenter run the analysis routines during breaks, lunch, or in the evening. Use the results to develop questions for the workshop to ensure completeness before the end of the workshop. Take advantage of the analysis capabilities of the tool, but do not run the analysis with the participants waiting for you to finish.

- Make certain that adequate backup is provided (both software copies and manual backup to cover the period of time since the last copy was made). Automated tools sometimes crash, or electricity sometimes goes out. Do not be caught losing documentation.

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Dec 22, 2016 | Facilitation Skills

Great Facilitators

Today we bring you twelve significant behaviors that define successful, professional facilitators. (i.e., GREAT Facilitators) Our scope focuses on structured facilitation (NOT Kum-Bah-Yah). Structured facilitation requires a balanced blend of leadership, facilitation, and methodology. (An alpha sort sequences the following, not order of importance).

The first three behaviors:

- 7:59 AM preparation and interviews

(i.e., managing expectations and ownership). Increased experience forces top-notch facilitators to value preparation more than ever. No class, certification, or silver bullets help facilitators who show up without preparation.

- Active listening

(i.e., seeking to understand rather than being understood). Of facilitation’s core skills, active listening remains the easiest to understand and the hardest to do.

- Annotated agenda

(i.e., visualizing everything the session leader does or asks in advance). Preparation or writing down what you intend to say and do remains critical. Therefore, Great facilitators don’t rely on memory, they write it down.

The next three behaviors:

- Common nouns and purpose give rise to natural categories

. A professional NEVER asks a group HOW they would like to ‘categorize a list.’ Common nouns are symptomatic of the likelihood of clusters. Normally categorizes arise from shared or common purpose.

- Holarchy

(i.e., interdependent reciprocities—contextual explanation of how it all fits together). When active listening fails to resolve conflict, appeal to the organizational objectives. They drive the determination of whose argument should prevail. Begin with the project, then the program, then the business unit, and if necessary, enterprise objectives. The holarchy provides the key to alignment and a professional knows how to apply it.

- “I” no longer

(i.e., the substitution of pluralistic and integrative rhetoric for the first person singular). Professionals avoid reference to themselves alone. Everything ‘we’ do is for the benefit of them and you, not ‘me.’ The least professional words a facilitator could utter — “Help me.”

Three more behaviors:

- Life Cycle: Plan ☛ Acquire ☛ Operate ☛ Control (i.e., great tool and inherent rationale behind all life cycle methodologies). It matters not whether building requirements or an action plan. Blue-chip facilitators explore at least four activities (likely more). They ensure at minimum one activity within each of the four primary life-cycle stages.

- Numeric SWOT leads to consensual actions (i.e., Easily the best way to prioritize hundreds of items and build consensus around “WHAT” needs to be done to support the purpose). So many untrained facilitators build four lists, hang them on the wall, and ask “Now what?” Traditional SWOT remains an awful method for galvanizing consensus. Outstanding facilitators consider the MGRUSH quantitative approach instead.

- Right-to-left thinking or, focus on the deliverable first (i.e., starting with the end in mind—forcing the abstract into the concrete). Leadership demands understanding what ‘DONE’ looks like. Top-flight professionals constantly apply a ‘DONE’ consciousness against the meeting deliverable, agenda step, supporting activity, and even specific questions. Always start with the end in mind.

The final three behaviors:

- “The Purpose is to . . . So That . . . “

(i.e., an amazing tool to extract the “strategy” behind something too small for a

“strategic plan”). The professional facilitators’ ‘screwdriver.’ is known simply as the Purpose Tool. Use it repeatedly to first build consensus around WHY something exists before discussing WHAT can be done to make it better.

- Trivium

(i.e., the natural force behind the structure of movement and progress). Plato called it Logic, Rhetoric, and Grammar. Our sixth-grade teachers called it WHY, WHAT, and HOW. Project life cycles are called Planning, Analysis, and Design. We call it Will, Wisdom, and Activity. The Trivium represents the nature of structured facilitation as superb facilitators help groups transform from the abstract to the concrete.

- Website resources

(i.e.,” You get to ride all the rides, as many times as you want.”). You will find many of the finest facilitators in the world among the thousands of MGRUSH alumni. Therefore, use online access to agendas, templates, and other meeting support tools to make your life easier.

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Dec 15, 2016 | Managing Conflict

Group decision-making, when not transparent or properly facilitated, can lead to awful decisions. The Abilene Paradox captures why four intelligent adults would agree and decide to do something that none of them wanted to do in the first place.

It may sound absurd that four intelligent adults would agree and decide to do something that none of them wanted to do in the first place, but it is effectively found in a small but well-received story. I first learned of Harvey’s article while receiving my MBA at Kellogg, and was recently reminded of it during a discussion with a student after class, who was in the process of earning her own MBA.

The Abilene Paradox Background

Based on a story that starts in the remote town of Coleman, Texas, four adults travel in a dust storm and 104 degrees (Fahrenheit) heat in an un-air-conditioned ’58 Buick to a cafeteria in Abilene. After returning, the story covers their conversation which could be summed up with the comment “ I didn’t want to go.” Of course, none of them did, so why did they go?

Jerry B. Harvey’s Abilene Paradox tale can be found sourced in the October issue of the Organizational Dynamics journal, 1985. Its message is timeless. He identifies the inability to manage agreement as a major source of organizational dysfunction. He never mentions the need or value of a professionally trained facilitator. Rather, he describes the caller of the meeting as the “confronter.” A professionally trained facilitator provides a more effective term as they should challenge participants (rather than “confront” them).

Therefore, in his article, Harvey covers six issues.

Six Abilene Paradox Lessons

The Abilene Paradox

- Symptoms of the paradox (arguably the most important of the six)

- People in organizations shave private conversations . . .

- . . . and make private agreements as to the steps to “cope” with the situation or problem they face.

- They fail to communicate their underlying desires or beliefs to one another leading to a misperception of the collective reality.

- Members make collective decisions that lead them to take actions contrary to what they want to do, and thereby arrive at results that are counterproductive to the organization’s intent and purposes . . .

- . . . resulting in frustration, anger, irritation, and dissatisfaction with the organization that causes blame toward “other” subgroups.

- Since they are unable to manage agreements (rather than conflict), the cycle repeats itself with greater intensity.

- How they arise in organizations

- The underlying causal dynamics

- Implications for organizational behavior

- Recommendations

- Views toward the broader existential issue

The Abilene Paradox provides fun and enjoyment because his thesis asserts that the failure to communicate effectively runs rampant throughout most large organizations. Facilitated decision-making provides a dependable answer or alternative to absurd decision-making. Why? Because people speak symptomatically. Without proper challenge, they do not think clearly nor do they articulate the driving cause or rationale behind their beliefs.

The Watergate Paradox

Also citing the “Watergate” fiasco that brought down President Nixon, Harvey notes that . . .

“ . . . the central figures of the Watergate episode apparently knew that, for a variety of reasons, the plan to bug the Watergate did not make sense.”

Avoid your own Watergate, or an exhausting 106-mile trek by embracing the value of a trained, professional facilitator.

Remember that two people arguing about the spiciness of a chili or curry are both right. By title, they are called ‘subject(ive)’ matter experts. Your role as the facilitator through the method of the challenge will get them to agree that regardless of spiciness, the chili or curry measures 1,400 Scoville Units.

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.

by Facilitation Expert | Dec 8, 2016 | Leadership Skills, Meeting Structure, Meeting Support, Meeting Tools

Here’s how to create a project plan or RACI chart (or RACI matrix) when your discussion or meeting deliverable includes assignments for actions that have been built or identified.

As a result of capturing the additional inputs below, you develop a consensual understanding from your group’s roles and responsibilities chart (RACI chart).

(1) WHO will take responsibility (the keystone of a RACI chart or RACI matrix) for

(2) WHAT needs to be done (ranging from simple activities to comprehensive strategies) and

(3) WHEN the assignment(s) may be completed, given resources such as

(4) HOW MUCH extra money (approximate cash or assets) required and

(5) HOW MUCH estimated labor (FTP, or full-time person) is required to complete the assignment?

RACI Chart – Roles and Responsibilities

RACI Chart – Roles and ResponsibilitiesMethod for Building a Roles and Responsibilities Matrix[*]

The WHAT group of actions or assignments may take the form of strategies, initiatives, programs, projects, activities, or tasks. They should already be identified before beginning your RACI or RASI assignments. Furthermore, as you increase the resolution from the abstract (eg, strategy) to the concrete (eg, task), expect to increase the resolution of the role or title of the responsible party. For example, strategies may get assigned to business units while tasks get assigned to individual roles such as Business Analyst or Product Owner.

Remember that the WHO dimension might include business units, departments, roles, or people but be consistent and match closely to the appropriate level of responsibility for WHAT needs to be done. Define each of the (five) areas of responsibility—note that each implies the others that follow. For example, the Authorizer is also Responsible. Hence, because they Support the effort, they need to be Informed about it as well.

- A = Authorizes—approves or signs off on the method or results of a given task

- R = Responsible—is held responsible for the success and completion of a given task

- S = Supports—provides assistance, information, etc., in the completion of a task—if requested

- C = Consults—provides consultation as required

- I = Informed—is kept informed of the progress or results of a given task.

- L = Lead (a surrogate or substitute for R)

Rules to Follow When Building a Roles and Responsibility Matrix

Especially relevant, note that C, or Consults has been de-emphasized with a blue font because “consults” can be a nebulous term. Our advice suggests substituting the S because it implies both Supporting and Being Informed.

Consider building your RACI chart or matrix using a large sheet of paper. Use a bright color marker, red is optimal, to document the R. Go back and complete the other relationships as appropriate.

- Portrait view—When using an easel or flip chart, write the people involved (units, job names, etc.) across the top (the WHO) and the tasks, jobs, projects, etc., down the left-hand side (the WHAT).

- Landscape view—Build a matrix on a whiteboard or other large writing area with the tasks, jobs, projects, etc. (the WHAT) across the top and the people involved (units, job names, etc.) down the left-hand side (the WHO).

- One and only one R per row (i.e., for each activity)

- At least one A who is not the R—may be more than one

- When this role requires only to be informed

- S for those supporting the R

NOTE:

- A implies R, S, I

- R implies S, I

- S implies I

Because this approach develops input for a Gantt chart, you also build consensual understanding and shared ownership. Furthermore, a facilitated effort captures the group’s personality, not a lone myopic view from one person’s office or cubicle. A generic and illustrative Gantt chart follows, displaying activities and assignments supporting a faux product development project:

An Infographic GANTT Chart

How to Build Roles and Responsibilities for Multiple Sites

Here is a roles and responsibilities matrix that can help you manage multiple sites. The following supports more complicated situations than the traditional RACI chart (or RACI matrix or its equivalent) discussed above.

Roles and Responsibilities for Multiple Sites

Using the table above as an illustrative template, preview the content you need to facilitate and develop. The content is coupled with additional explanations of the column headings below that support multiple sites.

Activity or Task[*]

The first section provides details about the Activity or Task that needs to be assigned and completed. Since the details will not fit comfortably into a spreadsheet cell, code the cell and refer to another document with additional details. As the details may or may not be complete at the time of the assignment, there may be a separate individual or group who takes on the role of author and provides the details. When initially logged, the details are either complete (y for yes) or not (n for not).

Location

Since identical tasks may be carried out in multiple facilities, code the facilities in the Location section. There could be more than two facilities of course. If more than two, you might substitute “A” for all instead of “B” for both.

Who Does What

The WHO section captures who will be responsible for the activity or task at each respective location. If necessary, you can add an additional column indicating their backup or who may be supporting them.

Frequency

The Frequency section refers to how often the activity or task needs to be performed. The due date represents the completion of the activity or task. For repetitive activities or tasks, the coding shown suggests the following:

- W = weekly

- M = monthly

- Q = quarterly

- A = annually

- V = variable or ad hoc

FTP or Full-time Person

The last section captures the intensity or concentration of effort required to complete the task. While frequently shown as hours per month, you could substitute FTP (i.e., full-time person-equivalent) or whatever measurement works best in your culture (aka FTE or full-time equivalent).

Finally, append the table with a resource column that estimates how much financial capital or currency will support the activity or task. This is a tool that you can modify to your situation, cultural expectations, and terms—so experiment freely.

A Roles and Responsibilities Matrix (RACI Chart) Captures WHO Does WHAT By WHEN

We have discovered at least twenty (20) different varieties of the Responsibility Matrix. While methodologically agnostic, we support any method your culture uses. However, be careful with the “C” as in ‘consult’. Because one can never be certain if an assigned “C” provides you something or you provide them something. Below you will find 20 documented types of roles and responsibilities, and undoubtedly there are others:

Transform Roles and Responsibilities Into a GANTT Chart

Click here to see a recorded demonstration of how to transform your roles and responsibility matrix into a Gantt chart.

- ARCI

- RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consult, Informed)

- RACIA (Approve)

- RASI (Supports)

- RASCI

- PARIS

- ALRIC

- RASCIO (Omitted)

- LACTI (Lead, Tasked)

- AERI (Endorsement)

- RACI-V

- CAIRO

- DRACI (Drives)

- DACI

- DRAM (Deliverables Review and Approval Matrix)

- RACIT

- RASIC

- RACI+F, where F stands for Facilitator

- CARS (Communicate, Approve, Responsible & Support)

- PACSI (Performed, Accountable, Control, Suggested & Informed)

[*] Moreover, for a thorough primer and clear discussion on RACI, see “RACI Matrix: How does it help Project Managers?”

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Related video

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.