Searching for a problem solving approach proven to work in a variety of situations?

Whether you’re a group of highly paid nuclear physicists designing a new multimillion-dollar scanner or a group of unpaid volunteers supporting the growth of a children’s choir, you need to know how to move collaboratively from where you are to where you need to be.

So How Do You Get There?

So How Do You Get There?

There’s more than one right method for effectively leading groups and teams down an optimal path. First, however, be extremely cautious and avoid beginning your meeting or workshop with analysis, unless you have already clearly agreed on a purpose (i.e. Why do we need a solution?)

Most approaches to problem-solving assume a common, pre-existing purpose—but an effective meeting facilitator presumes the opposite. They work with the assumption that most groups lack a clear, coherent, and consensual purpose, the WHY before the WHAT. Yet secondary research shows that most problem-solving approaches include only the following steps (parenthetical comments reference the paragraph below):

- Problem identification (frayed collar)

- Problem diagnosis (socially embarrassing)

- Solution generation (click or brick options)

- Solution evaluation (apply preferences)

- Choice (selection)

Using a simple example in our private lives, we may identify (1) a frayed collar on our favorite shirt or blouse. (2) The collar scratches and could potentially be socially embarrassing to wear. (3) One solution would be to go a click or brick store where we can find assorted options on the screens and shelves. (4) Applying our preferences for brand, color, price, size, etc., (5) we make our selection.

Yet even a Frayed Collar Requires Purpose When Problem-Solving!

It’s just a collar–right? True, and if you were purchasing the shirt for yourself you would already know the purpose. However, imagine you hear your dad complaining that he needs a new shirt because his collar is frayed and he’s embarrassed to wear it (steps 1 and 2). Wanting to please him, you ask him what his favorite clothing store is, what size he needs, short sleeve or long sleeve, and what color he prefers (steps 3,4, and 5). Then, armed with this knowledge, you purchase a new medium white shirt from his favorite store, but when you hand it to him he frowns and says, “Thanks, but I can’t wear this white golf shirt to my best friend’s formal wedding.” What did you forget to ask? The purpose!

Although our purpose strongly influences our selection, consensually articulated purposes are usually omitted from problem-solving methods. Why? Because most educators lack experience leading meetings. Bottom line: As the meeting leader, or facilitator, you must build consensus around WHY we are doing something before you analyze WHAT should be done (and eventually, HOW to do it).

Conflict in Problem Solving

We have seen meetings begin to unravel until we re-direct or help the group build common purpose. Without common purpose, there is no common ground managing arguments and, with limited resources, making the necessary trade-offs or exclusions.

Common Purpose Sets Up an Integral, Win-Win Result

Every problem-solving method yields different consequences when measured by team ownership (risk) and decision quality (reward). Risk-reward is optimized when you first establish common purpose. If you fail to facilitate agreement about purpose before you tackle the problem, you risk compromise, voting, or withdrawal. The different methods of solving problems include:

- Compromise (lose-lose),

- Forcing (voting; i.e., win-lose),

- Integrative (win-win), or

- Withdrawal (quit)

Use the problem-solving framework below and you will discover that ownership and decision quality begin with a common purpose. Please keep in mind that leading a group from ‘here’ to ‘there’ posits more than one right answer. Therefore, facilitation strives to articulate the best answer for each group of participants, given their situation and constraints.

Integrative Problem Solving Framework — Many to Many Meeting Design

This Problem-Solving Approach facilitates groups by enhancing focus when there are many symptoms, causes, preventions, and cures that might be considered. This will also help you keep certain participants ‘on track,’ especially those who tend to jump around, or love to opine.

Many meetings waste time because they lack structure, not because they fail to generate some promising ideas. Meetings are challenged by the fact that teams never know when they are done, how they can measure progress, or how much work remains to be done. They don’t know what they’ve missed. And because they don’t know what they don’t know, it takes a disciplined approach to structure activities and ask precise questions that unveil hidden solutions.

Problem Definition

The first part of meetings should not actually try to solve the problem but find diverse ways of looking at and describing the problem situation. The more general the expression of a problem, the less likely it is to suggest answers.

NOTE: The problem definition remains far more critical than most people understand. For example, an automobile traveling on a deserted road blows a tire. The occupants discover that there is no jack in the trunk. They define the problem as ‘finding a jack’ and decide to walk to a station for a jack. Another automobile down the same road also blows a tire. The occupants also discover that there is no jack. They define the problem as ‘raising the automobile.’ They see an old barn, push the auto there, raise it on a pulley, change the tire, and drive off while the occupants of the first car are still trudging towards the service station.

Although Getzels does not mention a third option, note how another group might push the vehicle to the side of the road and using their hands, rocks, sticks, or other implements, dig a hole around the bad tire. Their problem statement reflects the need for clear access to the axle and surrounding area, rather than lifting the vehicle. No doubt there is a fourth or more problem definitions as well.[1]

Two Highly Effective Problem Definition Methods

The surest way to create divergent solutions is to diverge descriptions of the problem. When focused on describing the problem, using mountaineering as an analogy, consider:

- Re-writing or versioning diverse ways of stating the problem.

-

- Broaden focus, restate the problem with the larger context

-

-

- Initial: Should I keep a diary?

- Broadened: How do I create a permanent memory of our ascent?

-

-

- Paraphrase, and restate the problem using different words without losing the original meaning

-

-

- Initial: How can we limit congestion around the base camps?

- Paraphrase: How can we keep the congestion from growing?

-

-

- Redirect focus, consciously change the scope

-

-

- Initial: How do we get all our supplies to 16,000 feet?

- Redirected: How do we reduce our consumption and need for supplies?

-

-

- Reversal, turn the problem around

-

-

- Initial: How can we get people to go to a different mountain?

- Reversal: How can we discourage people from climbing this mountain?

-

- Changing perspectives to stimulate worthwhile aspects that further help detail and describe problems. Examples of mountaineering perspectives might include the climber, sherpa, legal authority, other climbers, etc. Your own questions may be toggled among thirty or more established business perspectives found detailed HERE.

Structuring Your Problem-Solving Approach

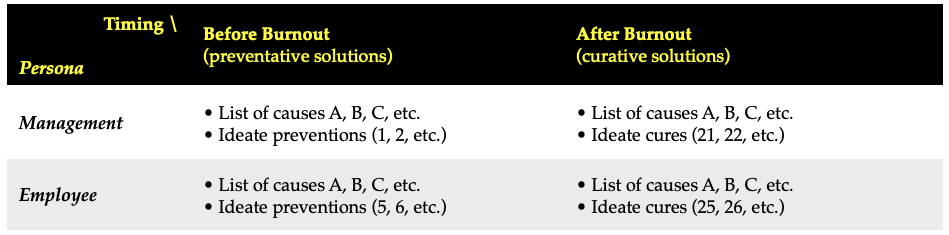

You need to structure and focus discussions to get more done quickly, especially when there are many symptoms, causes, preventions, and cures that should be considered. Therefore, with a complex problem, I’ll use the following as an example.

Illustrative Example

Let’s use the example of an organization that has determined that a problem of ‘Burnout’ exists in their IT Service Department. We will use the Problem-Solving Approach to draft a solution.

Workshop Deliverable

A solution built around proposed actions that will prevent, mitigate, and cure the causes of ‘Burnout’ within the IT Service Department.

Fundamental Problem-Solving Agenda

- Introduction

- Purpose of the IT Service Department (Description of Ideal) — Confirm the purpose of the solution state or the ideal condition. Describe the way things ought to be when there is no problem, and everything is working properly according to design.

- ‘Burnout’ (Definition of Problem) — Fully define the problem state or condition, building consensus around the way things are at present.

- Symptoms (Externally Observable Factors) — Identify all the potential symptoms that make it easy to characterize the problem or issue. Consider symptoms to be factors that can be seen and observed objectively, such as “tardiness.”

- Causes (Conversion) — For each symptom identify one or many possible causes or consider Root Cause Analysis (aka Ishikawa Diagram).

- Actions — Populate a matrix with the agents against a timeline as shown in the Solution Stack below. The simplest way to approach the ‘x’ dimension is to separately cover actions before and after causes (such as what can be done to prevent each cause and what can be done to cure for each cause, by each agent).

-

- First note WHO participates in the solution — Identify persona: people, agents, or actors that will participate in the solution or plan (eg, participants, management, contractors, etc.).

- IT Service Department Personnel (y-axis, Persona A)

- Management (y-axis, Persona B)

- Using a timeline, identify WHAT actions to take — With the group at large or assigning breakout teams, develop potential responses and actions with each persona across the timeline using each cause, one at a time.

- Preventions [x-axis, Timeline 1]

- Cures [x-axis, Timeline 2]

- See below for questions to ask to generate actions.

- First note WHO participates in the solution — Identify persona: people, agents, or actors that will participate in the solution or plan (eg, participants, management, contractors, etc.).

Questions to Ask to Generate Actions

If you embrace this structured tactic, you know exactly what to do and what four questions you must ask for EACH cause (e.g., fatigue):

-

-

- What can technicians do to prevent fatigue?

-

-

-

-

- (e.g., Improve their diets, etc.)

-

-

-

-

- What can management do to prevent fatigue?

-

-

-

-

- (e.g., Provide ergonomic furniture, etc.)

-

-

-

-

- What can technicians do to cure fatigue?

-

-

-

-

- (e.g., Get to bed earlier, etc.)

-

-

-

-

- What can management do to cure fatigue?

-

-

-

-

- (e.g., Hire more resources, etc.)

-

-

Which one of these four questions can you afford to skip? None of them of course because you don’t know which ones, if any, you can afford to skip.

Solution Stack

I know this table gives a lot of people headaches. However, to be thorough, participants must answer all four questions about each cause. Sometimes the reaction is “Screw it. Let’s just have a meeting and discuss it.” But how are those unstructured discussions working out for you? Don’t forget that the terms discussion, percussion, and concussion are all related. If you have a headache when you depart a meeting, it’s because the meeting was not structured and you’re not sure what, if anything, was accomplished.

______

[1] Getzels, J.W., Problem Finding and the Inventiveness of Solutions, Journal of Creative Behavior, 1975, 9(1), pp 12-18.

______

Don’t ruin your career by hosting bad meetings. Sign up for a workshop or send this to someone who should. MGRUSH workshops focus on meeting design and practice. Each person practices tools, methods, and activities daily during the week. Therefore, while some call this immersion, we call it the road to building high-value facilitation skills.

Our workshops also provide a superb way to earn up to 40 SEUs from the Scrum Alliance, 40 CDUs from IIBA, 40 Continuous Learning Points (CLPs) based on Federal Acquisition Certification Continuous Professional Learning Requirements using Training and Education activities, 40 Professional Development Units (PDUs) from SAVE International, as well as 4.0 CEUs for other professions. (See workshop and Reference Manual descriptions for details.)

Want a free 10-minute break timer? Sign up for our once-monthly newsletter HERE and receive a free timer along with four other of our favorite facilitation tools.

Go to the Facilitation Training Store to access proven, in-house resources, including fully annotated agendas, break timers, and templates. Finally, take a few seconds to buy us a cup of coffee and please SHARE with others.

In conclusion, we dare you to embrace the will, wisdom, and activities that amplify a facilitative leader. #facilitationtraining #MEETING DESIGN

______

With Bookmarks no longer a feature in WordPress, we need to append the following for your benefit and reference

- 20 Prioritization Techniques = https://foldingburritos.com/product-prioritization-techniques/

- Creativity Techniques = https://www.mycoted.com/Category:Creativity_Techniques

- Facilitation Training Calendar = https://mgrush.com/public-facilitation-training-calendar/

- Liberating Structures = http://www.liberatingstructures.com/ls-menu

- Management Methods = https://www.valuebasedmanagement.net

- Newseum = https://www.freedomforum.org/todaysfrontpages/

- People Search = https://pudding.cool/2019/05/people-map/

- Project Gutenberg = http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page

- Scrum Events Agendas = https://mgrush.com/blog/scrum-facilitation/

- Speed test = https://www.speedtest.net/result/8715401342

- Teleconference call = https://youtu.be/DYu_bGbZiiQ

- The Size of Space = https://neal.fun/size-of-space/

- Thiagi/ 400 ready-to-use training games = http://thiagi.net/archive/www/games.html

- Visualization methods = http://www.visual-literacy.org/periodic_table/periodic_table.html#

- Walking Gorilla = https://youtu.be/vJG698U2Mvo

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.