One of the worst questions a facilitator could ask is “How would you like to categorize these?” They don’t know how. That’s why they hired you.

Categorizing and creating clusters of related items (or processes) makes it easier for a group to focus on their subsequent analysis and decisions. Learn the logic behind the secret now, when the challenge is how to categorize when facilitating.

Rationale for How to Categorize

The purpose of categorizing is to eliminate redundancies by collapsing related items into clusters or chunks (a scientific term). A label or term that captures the title for each cluster can be more easily re-used in matrices and other visual displays. Frequently we refer to the labels as “triggers” because they rely on a a single term for triggering back to the meaning and definition behind it. For example, “budgeting” refers to the activities and resources required to project, track, and balance accounts. When focused on “budgeting” the group is less likely to focus on the details of “accounts payable” “accounts receivable” or other discrete clusters. Categorizing also makes it easier for the team to analyze complex relationships and their impact on each other.

Method for How to Categorize

Categorizing can take little or much time, depending on how much precision is required, time available, and importance. The underscoring method suggested below is quick and effective. The other methods may also be effective, but probably not as quick.

Underscore Common Nouns

Take the raw input or lists created during the ideation step and underscore the common nouns (typically the object in a sentence that is preceded by a verb). Verbs typically precede the object in a sentence as in “pay bills”. Use a different color marker for each group of nouns. By pointing to the underscored terms, ask the team to offer up a term, simple phrase, or label that captures the meaning of each cluster.

(Optionally)

For verification or to manage items that are not underscored, ask “Why _____?” The logic and secret behind categorizing follows.

NOTE: Items that share a common purpose likely have a common objective and can be grouped together. Verify that each item is WHAT they are doing and not HOW it gets done. Ask “WHY do you do this?”. Write the purpose next to the item. Continue with the next pairing—if it has the same purpose, then it will group together. When a number of activities relate—due to common purpose—have the group name the cluster. Put a visual box around the name for the cluster.

Transpose

Ask for a volunteer to take the underscored items and create a new statement or gerund that combines, integrates, and reflects the sentiment of the commonly underscored items. Write the new statement or gerund expression that signifies a grouping on a new and separate page. The terms may be more fully defined and illustrated with the list of all items that belong to each cluster. Notice how salt, mustard, and chutney may be grouped as “condiments’ because they share a common purpose. Use the MGRUSH Definition tool to build a consensual and robust definition if required.

NOTE: Format clusters as “gerund-like phrases.” That is, a noun followed by a gerund (a verb acting as a noun and usually ending with “ing”, “ment”, “tion”, or “ble” including “able” and “ible”). Examples are “Order Processing” or “Account Management” or “Resource Generation” or “Accounts Payable”.

Avoid vague terms such as “Management Reporting”—that have no specific goal. If the group includes a number of challenging processes, write these as a side list of “concerns” and continue with additional activities. Revisit the problem areas or concerns later, after the group has developed some momentum.

Avoid letting the group simply define their organization. For example, insurance companies have a tendency to define their “processes” as Underwriting, Claim Adjusting, and Operations. What they do from a process perspective (regardless of how they are organized) is Risk Assessment, Claims Payment, Portfolio Balancing, etc.

Transposing requires artful patience. Remain highly fluid and flexible. Activities may move around and processes may be re-labeled. There is no universally correct answer. Seek the terms that work best for the group that you are serving. And as always, seek to understand rather than be understood.

Scrub

Go back to the original list and strike the items that now collapse into the new terms created for each cluster in the Transpose step above. Allow the group to contrast any remaining items that have not been eliminated and decide if they require unique terms, need further explanation, or can be deleted.

Here is another example of using activities for creating the processes that support the function of Mountaineering.

|

# |

Support Activities |

Result |

|

1 |

Perhaps part of the same process as Pack supplies such as Provisioning | |

|

2 |

Supports a process called Ascending | |

|

3 |

Supports a process called Sheltering | |

|

4 |

Determined to be HOW they support Sheltering because a tent is a concrete term and not an abstract concept | |

|

5 |

Supports a process called Navigating | |

|

6 |

Supports process called Navigating number 5 from above | |

|

7 |

Deemed to best support the Navigating process, rather than a stand-alone activity | |

|

8 |

Supports process called Navigating numbers 5, 6, and 7 from above | |

|

9 |

Also determined to be HOW they support Sheltering because fire is a concrete term and not an abstract | |

|

10 |

Supports process called Provisioning, along with number 1 from above | |

| etc. |

Comparison Review

Before transitioning, review the final list of clusters and confirm that team members understand the terms and that they can support the operational definitions. Let the team members know that they can add additional terms to the clusters later, but if they are comfortable with them as is, to move on and do something with the list, as it was built for input to a subsequent step or activity.

“Decomposing”

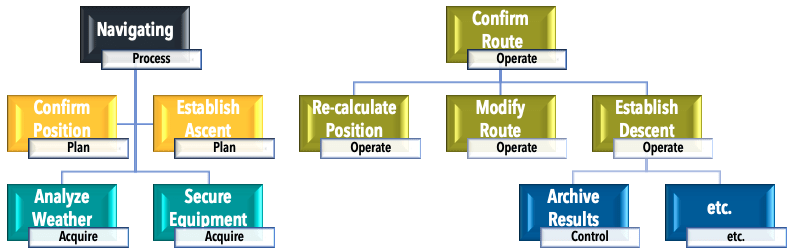

Once clusters or processes have been created, you can then further decompose into the various activities required to support the process. For example, with the process or cluster of “Navigating” we might find the following activities:

(In Conclusion, Other Grouping Themes)

Humans visually perceive items not in isolation but as part of a larger whole. The most frequent cause of categories is common purpose (e.g., gardening tools). However, the principles of perception include other human tendencies such as:

- Similarity—by their analogous characteristics

- Proximity—by their physical closeness to each other

- Continuity—when there is an identifiable pattern

- Closure—completing or filling in missing features

In a world where everyone can engage in decisions that affect them

______

Lead the Change—One Meeting at a Time

Are you ready to transform how decisions are made, problems are solved, and alignment is built in your organization?

True meeting leadership goes beyond setting an agenda. It requires a facilitator who can navigate complexity, balance voices, and drive toward outcomes with clarity and consensus. Our Professional Meeting Leadership Workshop and facilitation training equips you to do just that—blending human-centric methods with structured analytical tools to foster rigor, inclusivity, and results that stick.

- Practice live.

- Get expert feedback.

- Build confidence that lasts.

Whether your meetings suffer from unclear objectives, disengaged participants, or decision fatigue, this workshop will help you identify the root causes, apply proven facilitation techniques, and emerge as the leader every team needs.

Take the first step today—transform your meetings and magnify your impact.

👉 Click here to reserve your seat now.

#facilitationtraining #meetingdesign

Because every meeting should be a catalyst for change—not just another calendar event.

______

And earn up to 40 professional development credits with our facilitation training.

- CDUs (IIBA)

- CLPs (Federal Acquisition)

- PDUs (SAVE International)

- SEUs (Scrum Alliance)

- 4.0 CEUs (General Professions)

______

With Bookmarks no longer a feature in WordPress, we provide the following for your benefit and reference.

- 20 Prioritization Techniques = https://foldingburritos.com/product-prioritization-techniques/

- Creativity Techniques = https://www.mycoted.com/Category:Creativity_Techniques

- Facilitation Training Calendar = https://mgrush.com/public-facilitation-training-calendar/

- Liberating Structures = http://www.liberatingstructures.com/ls-menu

- Management Methods = https://www.valuebasedmanagement.net

- Newseum = https://www.freedomforum.org/todaysfrontpages/

- People Search = https://pudding.cool/2019/05/people-map/

- Project Gutenberg = http://www.gutenberg.org/wiki/Main_Page

- Scrum Events Agendas = https://mgrush.com/blog/scrum-facilitation/

- Speed test = https://www.speedtest.net/result/8715401342

- Teleconference call = https://youtu.be/DYu_bGbZiiQ

- The Size of Space = https://neal.fun/size-of-space/

- Thiagi/ 400 ready-to-use training games = http://thiagi.net/archive/www/games.html

- Visualization methods = http://www.visual-literacy.org/periodic_table/periodic_table.html#

______

Terrence Metz, president of MG RUSH Facilitation Training, was just 22-years-old and working as a Sales Engineer at Honeywell when he recognized a widespread problem—most meetings were ineffective and poorly led, wasting both time and company resources. However, he also observed meetings that worked. What set them apart? A well-prepared leader who structured the session to ensure participants contributed meaningfully and achieved clear outcomes.

Throughout his career, Metz, who earned an MBA from Kellogg (Northwestern University) experienced and also trained in various facilitation techniques. In 2004, he purchased MG RUSH where he shifted his focus toward improving established meeting designs and building a curriculum that would teach others how to lead, facilitate, and structure meetings that drive results. His expertise in training world-class facilitators led to the 2020 publication of Meetings That Get Results: A Guide to Building Better Meetings, a comprehensive resource on effectively building consensus.

Grounded in the principle that “nobody is smarter than everybody,” the book details the why, what, and how of building consensus when making decisions, planning, and solving problems. Along with a Participant’s Guide and supplemental workshops, it supports learning from foundational awareness to professional certification.

Metz’s first book, Change or Die: A Business Process Improvement Manual, tackled the challenges of process optimization. His upcoming book, Catalyst: Facilitating Innovation, focuses on meetings and workshops that don’t simply end when time runs out but conclude with actionable next steps and clear assignments—ensuring progress beyond discussions and ideas.